The leaflet is detailed below, or you can download the 'Genetic testing for BReast CAncer (BRCA) and PALB2 gene alterations' leaflet in PDF.

Introduction

Cancer is common in the general population with 1 in 2* people being diagnosed with a cancer in their lifetime, and most cancer occurs just by chance. Our suspicions of an inherited explanation for the cancers in a family are raised if the same or related cancers occur in several family members on the same side of the family, usually across different generations and at a younger age than expected. This is why genetic testing would be offered to a family.

*Cancer Research UK (2015) estimated lifetime risk of being diagnosed, people born after 1960.

What are genes and chromosomes?

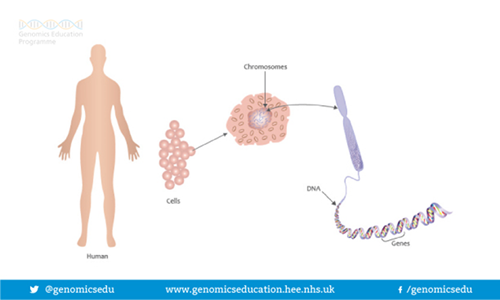

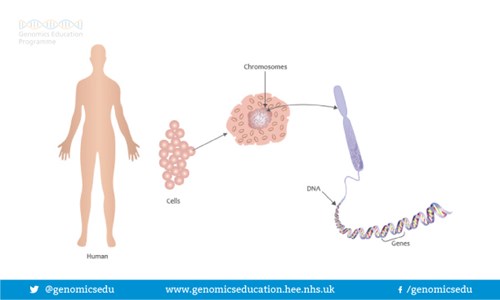

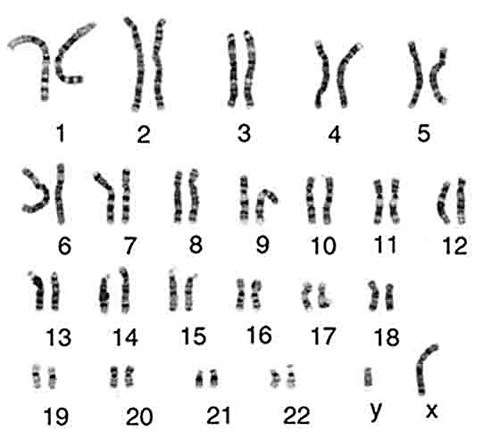

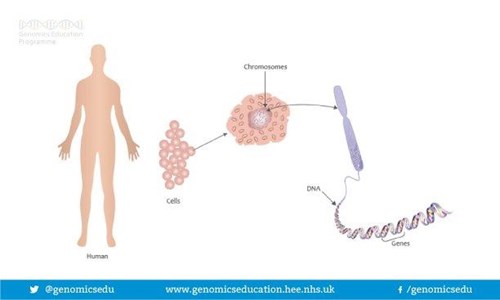

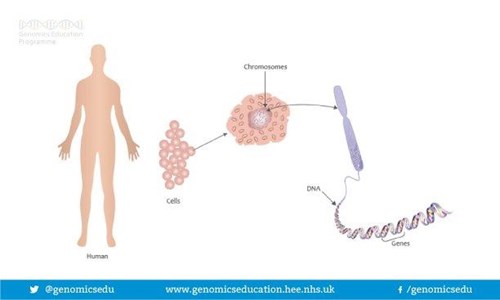

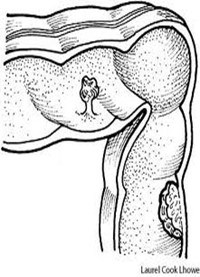

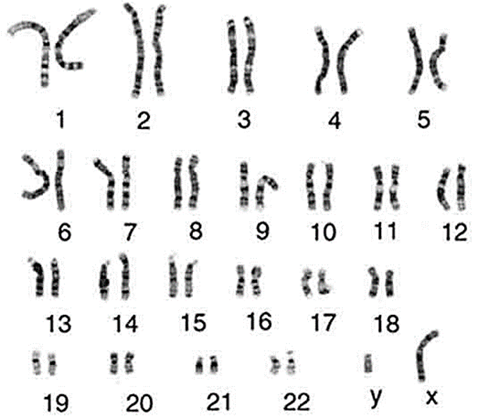

Humans are made up of trillions of cells. At the centre of almost all of your cells is a ball-shaped structure called the nucleus, inside of which are 46 thread-like structures called chromosomes. Chromosomes are long strands of DNA (DeoxyriboNucleic Acid). It is estimated that if a strand of DNA was stretched out, it would be around two meters long, even though the average cell is smaller than a pinhead.

Image Source: https://cpmc.coriell.org

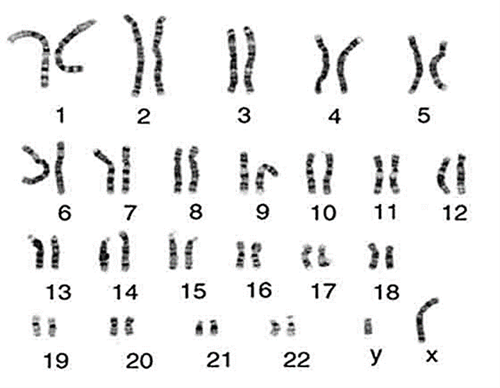

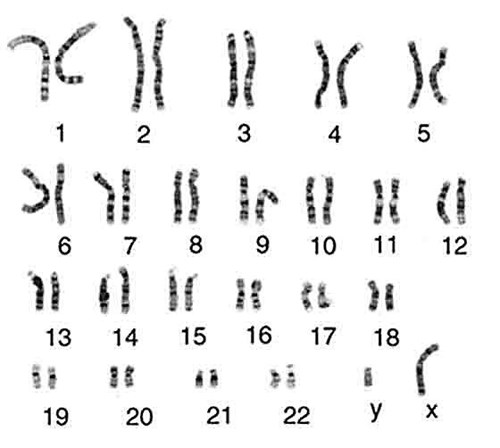

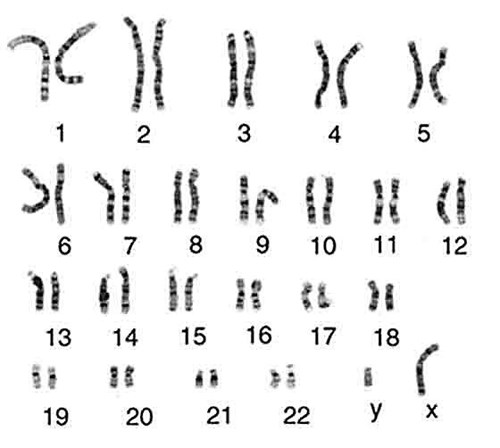

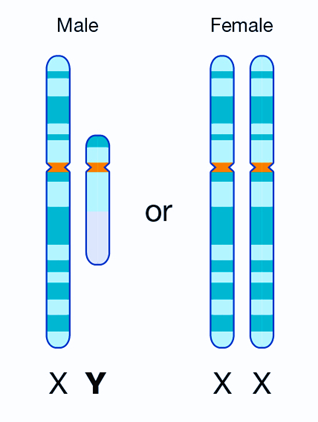

We have 23 pairs of chromosomes and one of each pair is inherited from each of your parents. Chromosomes 1-22 are arranged in size order with number 1 being the largest and 22 the smallest. The 23rd pair of chromosomes determines a person’s sex. Most males are XY and most females are XX. Chromosomes contain an estimated 20-30,000 pairs of genes that make us who we are. As we have pairs of chromosomes we therefore have pairs of genes.

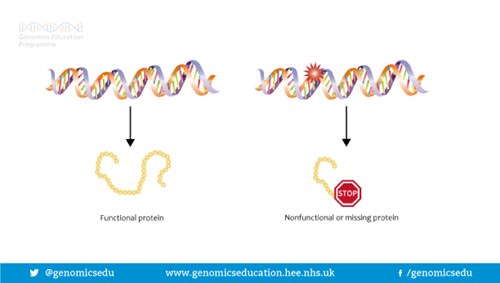

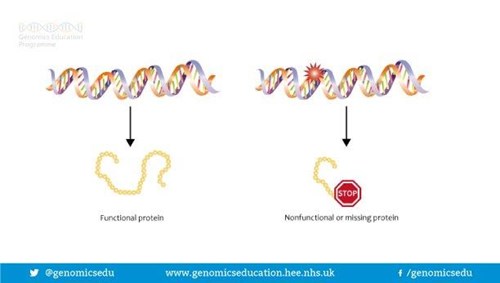

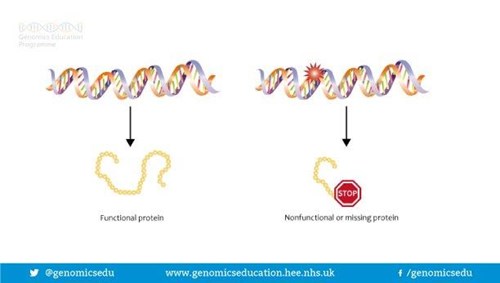

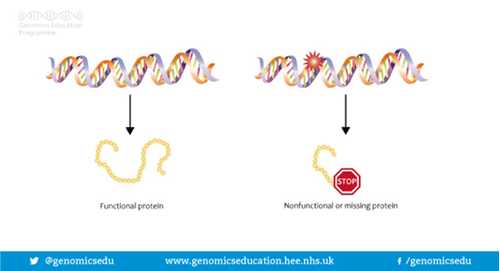

Genes are often called the blueprint for life because they tell each of your cells what to do and when to do it. For example, some genes determine how tall you will be; some what colour your hair will be; some genes are responsible for maintenance in our bodies and some for our development, and so on. Genes do this by making proteins. In fact, a gene may act by being a ‘recipe’ or a code for making a certain protein. In order for a gene to do the job it is supposed to do, the ‘recipe’ or code needs to be written correctly. If the ‘recipe’ is wrong, the protein is either not made, or is made incorrectly so cannot do the job it is supposed to do. This is sometimes called a gene alteration, a spelling mistake or a gene mutation.

What is the role of the BReast CAncer (BRCA) gene?

There are 2 BRCA genes that we know of and we all have 2 copies each of them. Our BRCA genes are known as BRCA1, which was the first BRCA gene to be identified, and BRCA2, which was the second BRCA gene to be identified. The role of our BRCA genes is to protect certain areas of the body from developing cancer. The BRCA genes are called tumour suppressor genes and the proteins produced from them help prevent cells from growing and dividing too rapidly or in an uncontrolled way. If there is an alteration in one of our BRCA genes then we have an increased susceptibility to developing cancer as we have less protection, but having an alteration in a BRCA gene does not mean a person will inevitably go on to develop cancer.

What is PALB2?

PALB2 is a gene that is known to be connected with breast cancer risk.

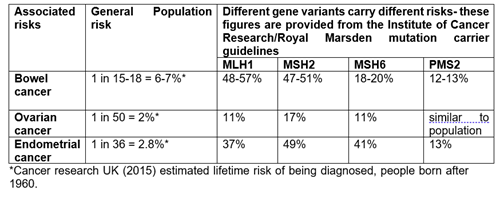

At present, if the cancers in a family are suggestive of having an alteration in one of the BRCA or PALB2 genes (the types of cancers associated with having a BRCA or PALB2 gene alteration are outlined in the tables below), we offer testing for alterations in these three genes. We are finding out about more genes all the time and it is possible that testing for different gene alterations may be available in the future.

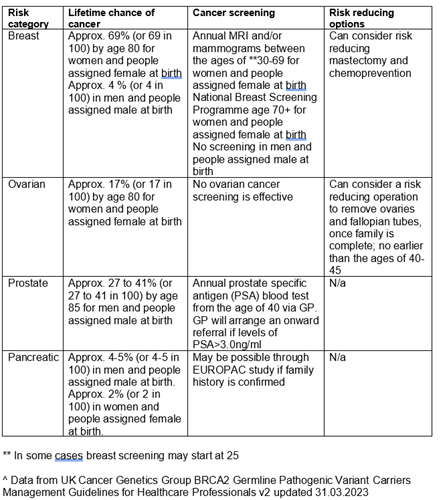

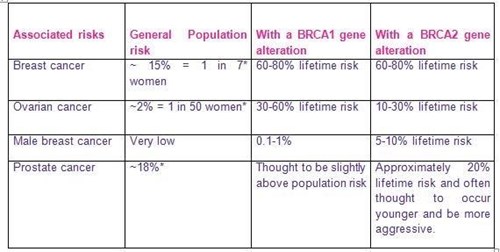

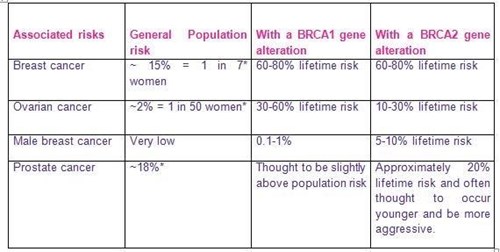

What are the main cancer risks associated with having an altered BRCA gene?

There are slightly different cancer risks associated with having a BRCA1 or a BRCA2 gene alteration:

*Cancer Research UK (2015) estimated lifetime risk of being diagnosed, people born after 1960.

There may also be a small risk of developing other cancers but not enough to warrant additional screening. However, it would be important to have a low threshold for seeking medical help for any concerning or persistent symptoms.

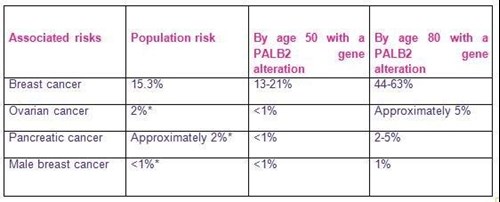

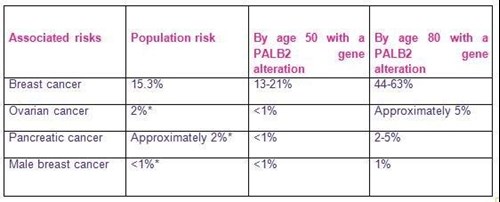

What are the main cancer risks associated with having an altered PALB2 gene?

What can be done to help manage these risks?

For each of the high risk cancers, screening and surgical options are discussed. Different options are available to men and women, and options can also differ dependent on what age you are.

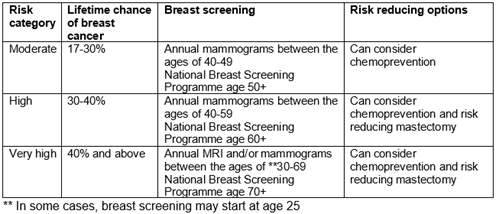

Breast screening

Women who have a BRCA or PALB2 gene alteration are offered high risk breast screening. This involves:

• Annual magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan from 25-39 years

• Annual MRI AND mammography from 40-50 years

• Annual mammography from 51-71 years (some women may continue to receive MRI too)

Women who have a 50% chance of inheriting a BRCA gene alteration but choose not to have a genetic test will be offered the screening described above until the age of 50. These women will then need to have genetic testing in order to continue to receive high risk breast screening, otherwise they will join the NHS Breast Screening Programme for a mammogram every three years.

For women who have a 50% chance of inheriting a PALB2 gene alteration but do not want a genetic test, their level of breast screening is worked out based on their personal family history.

Most NHS routine or high risk breast screening stops after the age of 70 or in some places 73. You can still have screening after this, and can arrange an appointment by contacting your local breast screening unit. This is something we would recommend if you were a carrier of a gene alteration. We also suggest that women carry out monthly self-examination of the breasts.

Men are not offered any breast screening, but we suggest they check their chest and armpit areas and seek medical advice for any unusual lumps.

Breast surgery

Women who have a BRCA gene alteration also have the option of having surgical removal of both breasts (bilateral mastectomy). Although this procedure could significantly reduce the risk of developing breast cancer, it will not remove the risk entirely. We also recognise this is a radical step that requires careful consideration. Therefore women who choose this option are fully supported throughout the process and not rushed into making any decisions. A booklet entitled ‘Understanding risk-reducing breast surgery’ by Cancerbackup is available from us which outlines the types of surgery available and possible outcomes. Please do not hesitate to ask for one if you think this will be helpful.

What preventative surgery options are available for people with a PALB2 gene alteration?

We know that your risk of cancer will vary according to your family history. If you have a strong family history of breast cancer you may wish to consider preventative surgery of the breasts (also called risk reducing mastectomy). If you have a close relative affected with ovarian cancer then preventative removal of the ovaries may also be an option to consider. Please talk to your Genetic Counsellor or Clinical Geneticist if you would like to look into this further

Ovarian screening and surgery for people with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene alteration

Ovarian screening involves regular blood tests approximately 3-4 times a year, to measure a marker in the blood called CA125, and annual ultrasound scan from the age of 35. However, ovarian screening often does not reliably inform us of cancers early enough in order for them to be treated effectively. Therefore, for women who are BRCA gene alteration carriers, over the age of 35 and who have completed their families we would encourage them to think about having their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). This can significantly decrease the risk of developing ovarian cancer and, also if undertaken around the age of 40, can reduce the risk of breast cancer. Again the risk of cancer is never removed entirely.

There are clear advantages to having your ovaries and fallopian tubes removed, however they do need to be weighed against the potential disadvantage of being put into an early menopause and the possible need for hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The advantages and disadvantages of HRT could be further discussed with a gynaecologist if you chose to go ahead with this process.

Chemoprevention

Recent guidelines have suggested that ladies at high risk of breast cancer can be offered chemo-prevention medications. Research suggests these medications can reduce the risk of developing breast cancer however they do have significant side effects. Please ask for a leaflet outlining the risks and benefits of chemoprevention if you think this is something you might be interested in.

Prostate screening for people with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene alteration

Prostate screening should be undertaken annually from the age of 40 in people who have a BRCA gene alteration. This can be provided through the GP.

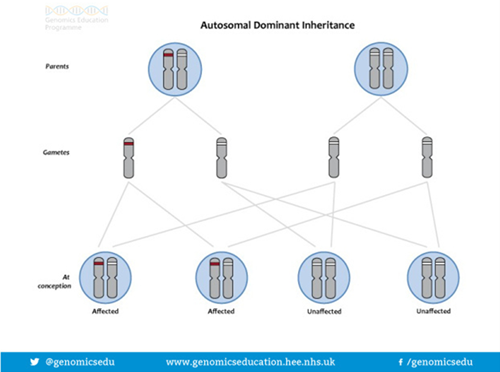

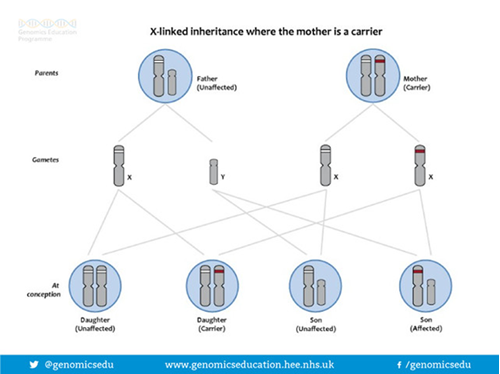

How are BRCA and PALB2 gene alterations passed down (inherited) through families?

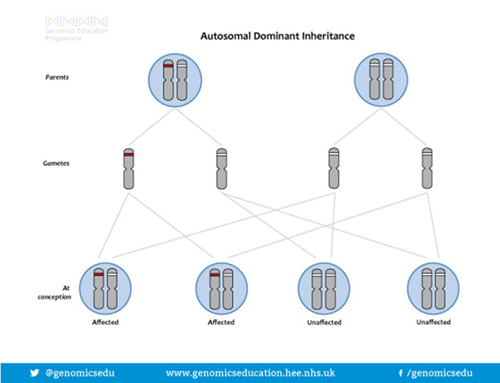

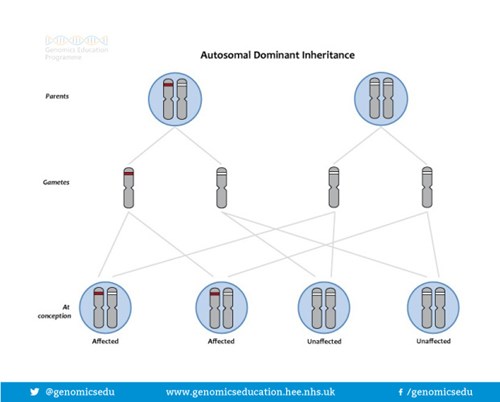

The way BRCA and PALB2 gene alterations are inherited is called DOMINANT inheritance. This is caused by an alteration in only one copy of the BRCA or PALB2 gene. Even though we each have 2 copies of the BRCA/PALB2 gene a normal copy cannot compensate for an altered copy and a person with one altered BRCA gene has an increased risk of developing cancer.

If a parent carries an altered BRCA or PALB2 gene, each of their children has a 50%, or 1 in 2 chance of having inherited the altered gene and therefore having an increased risk of developing cancer. For each child, regardless of their sex the risk is the same = 50:50

If I undergo testing for a BRCA or PALB2 gene alteration what will my results show?

Your results will show one of 3 things

- A gene alteration is identified in your sample that is known to be disease causing (pathogenic). This is highly likely to be the reason for the cancers in the family. If you have had a cancer this is called diagnostic testing. It also means you remain at risk of developing other cancers associated with having a BRCA or PALB2 gene alteration. If you have not had a cancer it means that you now have a high risk of developing BRCA or PALB2 related cancers. Finding a gene alteration allows other family members to be offered predictive testing. Predictive testing is offered to family members who are known to be at risk of inheriting a gene alteration that has been identified in the family but are currently well. Predictive testing is usually offered over a series of appointments to allow the opportunity to consider options and choices with time for reflection in between. How many appointments a person requires varies considerably from person to person and is negotiated on an individual basis with your genetic counsellor team. The overall aim of the predictive testing process is to help prepare a person for their results, whatever they are.

*NB: The finding of a pathogenic (disease causing) gene alteration is based on current knowledge. Very occasionally, new information in the future may mean that our understanding of the significance of a specific gene alteration may change*

No gene alteration is identified. This does not mean there is not an inherited genetic explanation for the cancers in the family, but it may be that within the confines of current technology we have been unable to detect a gene alteration, or that there may be an alteration in a gene that we do not yet know about and, therefore, cannot test for. Regardless of the results of any genetic testing we may still make screening recommendations for family members based on the family history to help protect their health.

For people who are undergoing genetic testing but who have NOT had a cancer: Please note that your result does not exclude the possibility that a BRCA or PALB2 gene alteration may be the responsible for the cancers in the family. Your result also DOES NOT provide any genetic information to anyone in the family apart from yourself and your children. In some circumstances we may be able to offer genetic testing to other family members as well. We will discuss this with you when we have your results.

A gene change has been found but we are not sure if it is significant or not. This is also sometimes called an unclassified variant (UV) or a variant of unknown significance (VUS). Finding this may mean we have to undertake more testing in the family or that we may need to look at the UV again sometime in the future to see if any further information about it is available. This will be discussed with you in more detail should this be the case.

What are the issues to think about when deciding whether or not to go ahead with genetic testing?

A genetic test can establish whether you have an alteration in a gene which could affect your health. It can be difficult to make a decision about whether or not to have a genetic test. We all have gene alterations and many of these do not affect our health. It is still quite unusual for a person to know they have an alteration in a specific gene.

There are reasons for and against having a genetic test. Within one family, relatives often have different views. You should try to make your own decision, without feeling pressured from relatives or other influences.

You will have plenty of opportunity to talk through the issues surrounding the test with the genetic counsellor or doctor. Some of the things people may consider include:

Do I need to tell people I am considering genetic testing?

It is entirely up to you whether or not you choose to tell anyone you are going ahead with genetic testing. It is often useful to have someone to accompany you to your appointments so that you have another ‘set of ears’ to hear the information and discussions that you have had. They can also be useful as a support for any discussions away from the appointment and should be someone you trust. People often choose this to be their partner, a close friend or another family member. However, if you choose to bring a family member it is important to remember the discussions you have in clinic are likely to have implications for them as well and they may not be prepared for this. Our experience, however, has demonstrated that families are often aware of the cancers and may already be asking questions about why and so it may be that an opportunity to discuss this within the family could happen quite naturally anyway.

Other people would rather wait until there is something to know before discussing things with the wider family, whilst other people prefer to discuss things as the process goes along to help prepare the family for any news. There are no right or wrong answers and we are happy to discuss how to involve your family if you wish.

Do my family need to know about any results I receive from genetic testing?

Genetic testing provides information for the individual but also will provide information for the rest of the family. If genetic testing identifies a gene alteration in you we would assume that you had inherited it from either your mother or father. Altered genes can often be passed down through families over generations without being noticed. Therefore, finding a gene alteration in you will have implications for other family members as well. So sharing genetic information in a family is really important. It can provide family members with a real opportunity to protect their health by enrolling in screening programmes to detect cancers as early as possible or even surgical options to help reduce the risk of developing cancer in the first place.

Sometimes people may think if genetic testing does not show anything then there is nothing to tell anyone. However, knowing what is happening in the family can prevent work being repeated as sometimes lots of family members are asking the same questions. It is also very important to remember that, regardless of the results of any genetic testing, the family history itself may mean family members are at a higher risk of cancer anyway and opportunities to protect their health can be offered to them.

How can I share this information?

On a practical level, you will have this leaflet to share with them and we will also provide a letter after your clinic appointment detailing any other issues discussed.

If a gene alteration is found we will provide you with a ‘relative’s letter’ detailing that a gene alteration has been identified in the family, that they are at risk and how to access testing. We will also guide you as to whom the letter should be passed on to.

On an emotional level, telling family members may be more difficult. You may be worried about upsetting them or have trouble deciding when the right time is. There really is no right or wrong answer to this but it is really useful to think about this before you get your test results and we are more than happy to discuss this with you further.

‘I won’t tell my children, it will only worry them.’

As parents, we want to protect our children from things that we believe can harm them and sometimes this means that we try and ‘hide’ things we think may be difficult for them to cope with. However, we tend to underestimate what children have already picked up on and they are often aware of something going on anyway. They may have noticed letters from the hospital or overheard conversations, they may also pick up cues from adults that they should not ask any questions.

Children in this situation may imagine something really awful is going on, often much worse than the reality, and may even believe it is something bad they have done.

Children value being included and are helped by adults who are honest and direct with communication. It is not always easy but children often cope a lot better than we give them credit for.

Our experience has also shown us that the parents of adult children often do the same. We are happy to talk to you about sharing information with your children during your appointment.

Who else should I tell?

That is entirely up to you. There is generally no obligation to tell your employer but it might be useful if you anticipate you may need time off work to have screening.

Having friends to discuss this with is helpful for some people but it is important to be aware that people may have differences of opinion that could be in conflict with any decisions you have made. However, for the majority of people, having discussions with other people is helpful and supportive.

What happens if I choose to go ahead and have a test?

After you have discussed what genetic testing could mean for you, you may decide to go ahead with testing. We will ask you to sign a consent form and we will take a blood sample from you.

The laboratory team will then search through the BRCA1, BRCA2 and PALB2 genes in your blood sample to see if the code in these genes differs from that of a normal gene. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are large and can take a long time to be looked through. We would expect results to be ready in approximately 3-4 months but please remember sometimes it can be more and sometimes less.

You can discuss with your genetic counsellor or doctor how you wish to receive your results. Some people want their results by letter or by telephone with the opportunity of a follow-up appointment to discuss any findings, whereas others prefer to come into clinic to have the opportunity to discuss the implications of any findings and next steps. This is entirely up to you and will be discussed during your appointment.

IF, FOR SOME REASON YOU, HAVE NOT RECIEVED YOUR RESULTS WITHIN 3-4 MONTHS AS EXPECTED PLEASE CALL THE LIVERPOOL CENTRE FOR GENOMIC MEDICINE ON 0151 802 5008.

Please remember to have your G number and W number handy for this call so we can quickly and correctly identify you.

What happens if I choose not to go ahead with having a test?

If you choose not to have a test, we may still make screening recommendations for your relatives based on the family history of cancer. However, we will not be able to offer predictive testing to your relatives.

Attending clinical genetics does not oblige you to go ahead with testing and, if you do go ahead and change your mind about receiving your results, you can do so until you are ready.

Other factors to consider

Insurance and Genetics

For some types of insurance it is necessary to provide medical information, including genetic information, to the insurers in order for them to set up your policy and work out your premiums. The types of policy that require a medical history or genetic test are likely to be, life cover, critical illness insurance and income protection insurance.

We would suggest that if yourself or family members are considering taking out new insurance policies in the future that consideration be given to the possible affect genetic test results could have on the ability to gain insurance or the premiums charged. Genetic Test results do not affect insurance policies already in place.

The Association of British Insurers (ABI) has a Code of Practice ‘The Concordat and Moratorium on Genetic and Insurance’:

• Insurance companies cannot ask for the Predictive Genetic Test results of individuals or family members (unless for Huntington Disease over £500,000). A Predictive Genetic Test is where an individual has a family member with a genetic condition, but who personally has no symptoms, signs or abnormal medical tests consistent with the condition at time of testing.

• If a family member has been diagnosed with a genetic condition based on a Diagnostic Genetic Test then you or family members will need to mention this when asked to provide your family’s medical history. In many cases Diagnostic Genetic Testing is used to confirm a diagnosis when a particular condition is suspected because of symptoms, signs or abnormal non-genetic tests including unusual findings on a routine blood test or other test.

Sources of Further Information on Insurance and Genetics:

The Association of British Insurers Genetics Frequently Asked Questions https://www.abi.org.uk/products-and-issues/topics-and-issues/genetics/genetics-faqs/

Genetic Alliance UK (Charity) Genetics & Insurance http://www.geneticalliance.org.uk/information/living-with-a-genetic-condition/insurance-and-genetic-conditions/

Useful Websites

Genetic Alliance UK www.geneticalliance.org.uk

Cancer Research group UK (CRUK) www.cruk.org.uk

National Institute for Health Care and Excellence (NICE) www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG41

All images in this leaflet were provided by NHS National Genetics and Genomics Education Centre

All images in this leaflet were provided by NHS National Genetics and Genomics Education Centre

Pic3

Pic3

How is the ATM gene alteration inherited?

How is the ATM gene alteration inherited?